By Michael Phillips | CABayNews

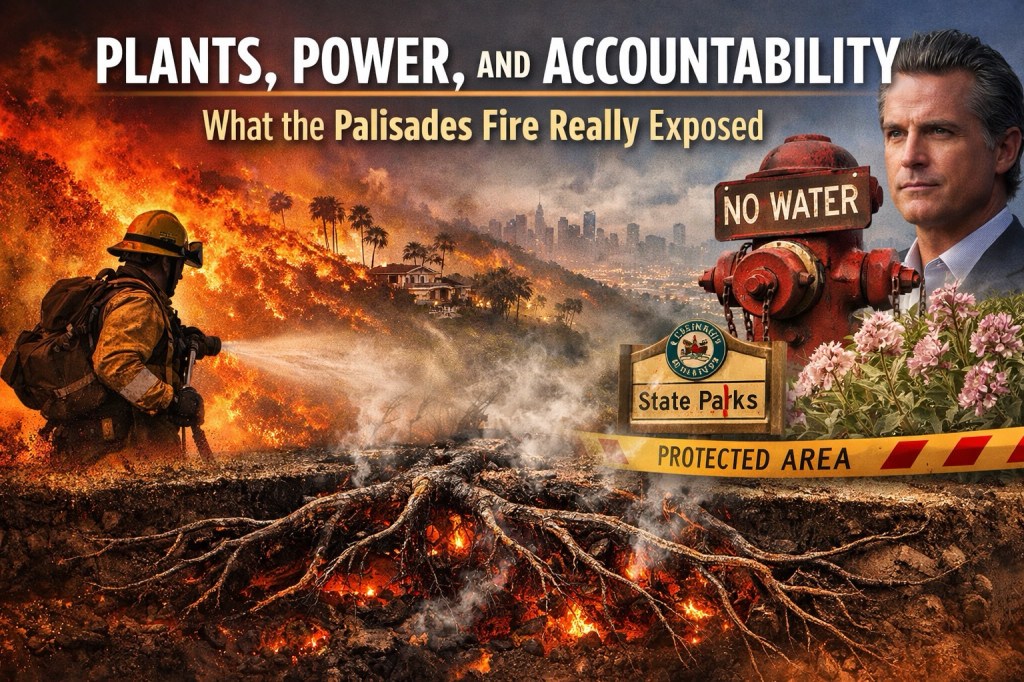

By any honest measure, the January 2025 Palisades Fire was not just a natural disaster. It was a policy failure layered on top of operational mistakes, infrastructure neglect, and years of regulatory choices that prioritized process and protection over urgency and accountability.

That is the uncomfortable takeaway from a recent investigation published by City Journal, the flagship magazine of the Manhattan Institute, which examined how a small, arson-ignited brush fire in Topanga State Park was allowed to smolder for nearly a week before erupting into one of the most destructive urban wildfires in California history.

More than 23,000 acres burned. Nearly 7,000 structures were destroyed. Twelve people lost their lives. Entire neighborhoods in Pacific Palisades were erased.

The fire did not begin as inevitable.

A Preventable Rekindle

Federal investigators confirmed the Palisades Fire was a holdover fire—a rekindling of the eight-acre Lachman Fire sparked by arson on New Year’s Day. While surface flames were declared contained, embers continued to burn underground in dense chaparral root systems. When Santa Ana winds arrived on January 7, the fire exploded.

Holdover fires are well-known in wildfire science. They require aggressive mop-up, monitoring, and follow-up patrols—especially before red-flag wind events. None of that happened here.

According to documents, text messages, and draft planning materials cited in the City Journal report, suppression efforts in Topanga State Park were constrained by California State Parks policies that emphasize ecological preservation, endangered plants, and cultural sites. Heavy equipment, fire retardant, and even full mop-up were discouraged or restricted in designated “avoidance areas.”

In text messages disclosed through litigation, one Los Angeles Fire Department supervisor wrote: “Heck no that area is full of endangered plants.” Firebreaks were allegedly undone after containment. No fire watch was posted for six days despite visible smoldering and worsening weather forecasts.

California State Parks denies it blocked firefighting and insists its role was merely advisory. Lawsuits will ultimately sort out who overruled whom. But the documentary record leaves little doubt that environmental rules shaped decision-making in ways that favored caution over certainty—plants over people, as critics have put it.

So Was This Gavin Newsom’s Fault?

Not directly—and not exclusively.

Governor Gavin Newsom did not decide to pull crews, skip monitoring, or leave a burn scar unattended. Those were operational failures involving LAFD and state agencies on the ground.

But Newsom does own the system that made those failures predictable.

For years, California leadership has advanced wildfire policy built around ecological sensitivity, regulatory compliance, and climate rhetoric—often at the expense of basic risk management in the wildland-urban interface. State agencies operate under overlapping rules that reward inaction, punish disturbance, and create fear of fines or liability for aggressive prevention work.

When a state fines Los Angeles nearly $2 million for damaging endangered plants during fire-safety operations—as it did in 2020—it sends a clear message. The result is institutional paralysis when decisive action matters most.

Blaming “climate change” after the fact, as state leaders often do, may be politically convenient. It is also incomplete. Wind and drought do not explain why a known ignition site went unmonitored for nearly a week.

Why Were the Hydrants Empty?

That failure is even harder to explain away.

The Santa Ynez Reservoir—critical to water pressure in the Palisades—had been taken offline for repairs years earlier and remained empty when the fire hit. As flames advanced, firefighters encountered dry hydrants in residential neighborhoods.

This was not an act of nature. It was infrastructure neglect.

The reservoir’s prolonged closure reflects another California pattern: deferred maintenance, regulatory delay, and bureaucratic inertia in a state that prides itself on climate leadership but struggles to deliver basic public works. A functioning reservoir would not have stopped the fire—but it could have slowed it, bought time, and saved homes.

The Larger Lesson

The Palisades Fire exposes a deeper problem than any single official or agency.

California has built a governance model where:

- Environmental compliance often outweighs emergency judgment

- Infrastructure failures are normalized

- Accountability is diffused across agencies

- Political leaders deflect blame to abstract forces

That model is increasingly incompatible with life in fire-prone, densely populated regions.

The choice is not between protecting nature and protecting people. It is whether California can design rules that recognize reality: when fire threatens homes, schools, and lives, suppression must come first—without hesitation, without fear of fines, and without waiting for permission.

Until that changes, the next “holdover fire” is already waiting.

Leave a comment