Why Are Los Angeles and San Diego Officials Blocking the Records?

By Michael Phillips | CABayNews / The Thunder Report

When government agencies—funded entirely by taxpayers—refuse to release records about an arrest, an investigation, or the conduct of their own personnel, the question is no longer just about paperwork. It is about power. It is about due process. It is about whether a person can receive a fair hearing in a court that depends on accurate information, proper procedure, and lawful investigative conduct.

And in the case of People v. Giselle Farias Smiel, unfolding simultaneously in Los Angeles and San Diego counties, those questions have suddenly become unavoidable.

Because records that should be public are being withheld. Agencies that are legally required to comply with the California Public Records Act (CPRA) are staging denials, delays, and quiet refusals. And the public is left to wonder: What exactly happened behind the scenes before the state decided to take away a woman’s freedom?

This is not a procedural dispute. It is a public-interest crisis.

Taxpayers Fund Law Enforcement. So Why Are Their Agencies Operating in the Dark?

California law begins with a premise: what the government does in the name of the people belongs to the people.

Gov. Code § 7921.000 states it plainly:

“Access to information concerning the conduct of the people’s business is a fundamental and necessary right of every person in this state.”

Yet in recent months, requests for records related to the investigation, arrest, and prosecution of Giselle Smiel have been met with:

- denials

- stalled responses

- vague extensions

- “records not found” claims

- shifting explanations across jurisdictions

The pattern spans multiple taxpayer-funded agencies:

- Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department

- San Diego County Sheriff’s Department

- Los Angeles County Superior Court administration

- San Diego Superior Court administration

- DCFS / child-welfare entities involved in related claims

- Deputy DAs and law-enforcement units that would ordinarily maintain routine investigative logs

Most of these agencies have been asked for straightforward records—dispatch logs, timeline documents, investigative affidavits, internal policies, arrest entries, CLETS audit trails, and administrative communications. Many of these are routinely released statewide.

Yet in this case, the public is being told to look away.

The Public Cannot Evaluate a Prosecution When the Government Hides the Foundation

A criminal prosecution is only as lawful as the process that produced it.

When an investigation contains errors, irregularities, or questionable conduct, public records serve as the corrective mechanism. They allow the public, the press, and the defendant to evaluate:

- whether probable cause truly existed

- whether officers followed constitutional guidelines

- whether the arrest entry was lawful

- whether the timeline matches witness statements

- whether key evidence was lost, delayed, or misrepresented

In Ms. Smiel’s case, those questions are central.

Conflicts in dates, arrest records, data entries, and courtroom statements already raise red flags about procedural accuracy. Yet the agencies responsible for those entries are refusing to provide the documentation that would resolve them.

This is not just a transparency failure.

It is an accountability failure.

Without those records, the public cannot know whether the prosecution stands on solid ground or whether the system is covering errors that could have wrongly altered someone’s life.

When Transparency Breaks, Due Process Breaks With It

The Sixth Amendment promises every defendant a fair process. That includes:

- clarity about the charges

- access to exculpatory information

- the opportunity to investigate

- the ability to challenge unlawful actions

But when key government actors refuse even basic record disclosures, the defendant’s ability to defend herself becomes compromised.

A justice system cannot demand blind trust.

If the government wants to restrict someone’s liberty, the government owes the public an explanation of how it arrived at that decision.

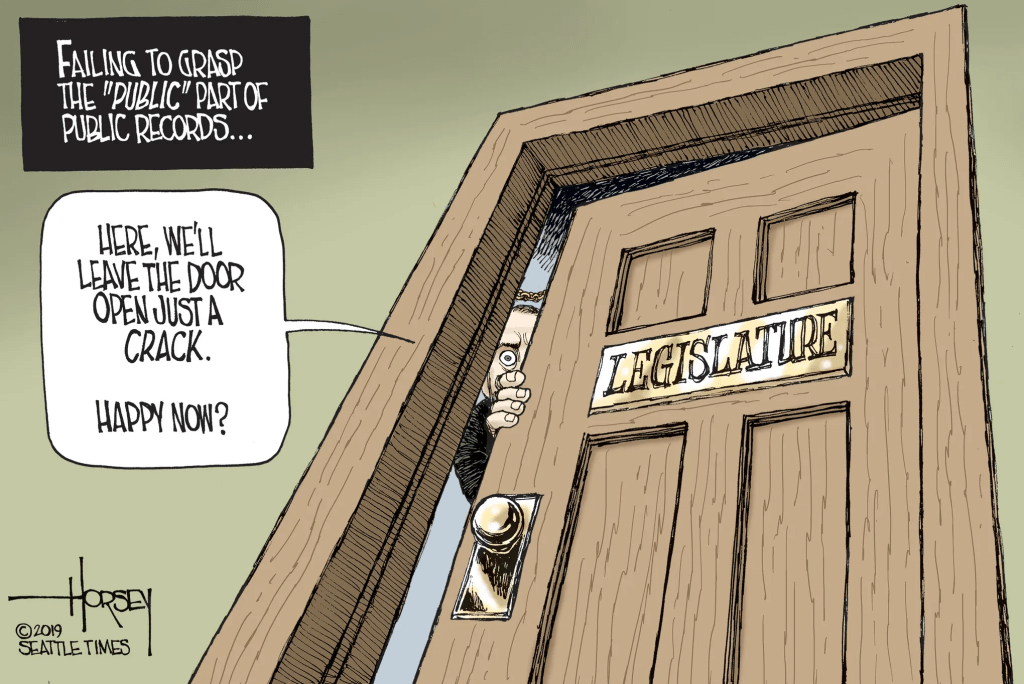

The CPRA was designed to make sure that process is visible. Instead, in this case, CPRA is being used as a shield for secrecy.

California Agencies Are Counting on Silence and Fatigue

Anyone who uses the CPRA regularly knows the pattern.

A citizen makes a lawful request.

The agency responds with a procedural delay.

Then another.

Then a claim that records do not exist.

Then a refusal to clarify.

Then a partial production that raises more questions than it answers.

This is not accidental.

Transparency advocates describe it as institutional exhaustion strategy—agencies count on requesters giving up.

But Giselle’s case shows the danger of that strategy when it intersects with criminal law. Silence and delay do not just frustrate citizens—they actively undermine a defendant’s ability to protect her rights.

The public has a right to ask:

If the records support the official narrative, why not release them?

The Human Cost of a System That Refuses to Let the Public See How It Works

A CPRA denial is not an abstraction.

It has real consequences for real people.

In this case:

- A mother facing serious charges cannot obtain public records related to her own investigation.

- Journalists attempting to verify the facts are being stonewalled.

- Supporters who attended her preliminary hearing were blocked from remote access due to unexplained courtroom switching.

- The public cannot confirm whether legal standards were followed on the day she was detained or the days she was released.

Transparency failures create fertile ground for miscarriages of justice.

They allow errors to harden into outcomes.

They leave the public with no way to separate the legitimate exercise of authority from the misuse of it.

This Should Not Be a Fight. It Should Be Routine.

Nothing requested in this case is unusual. Experienced records custodians across California routinely release the very same categories of documents that LA and San Diego agencies are refusing to produce here.

When the government follows the law, transparency is easy.

When the government does not, transparency becomes a threat.

That is why CPRA exists—to prevent silence from becoming a tool of power.

A State Cannot Withhold the Truth and Still Claim to Serve Its Citizens

California cannot tell its residents that the people’s business belongs to the people, then hide the record of that business the moment it becomes inconvenient.

And taxpayers should not accept a system in which the agencies they fund can shield themselves from oversight while they move to imprison a member of the public.

The core question is simple:

How can Californians trust a prosecution when the government refuses to let them see how the prosecution came to be?

Until Los Angeles and San Diego officials release the records, the public will not have answers.

And a justice system that hides the truth cannot demand public confidence.

Leave a comment